Please send any questions to the Secretariat of the Sea Cargo Charter Association at: info@seacargocharter.org

Background

The maritime sector has provided efficient economic services that have played a key role in enabling the growth of global trade and global economic development. However, this has not been without some adverse consequences unique to the maritime sector. The continued success of the maritime sector is intrinsically linked to the well-being and prosperity of society. Therefore, all industry participants must play a role in addressing adverse consequences.

The Sea Cargo Charter was developed in recognition of charterers’ and shipowners’ roles in promoting responsible environmental stewardship throughout the maritime value chain. It is a unique initiative that bridges international climate change commitments set out by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) with increasing corporate environmental expectations.

The Sea Cargo Charter was developed through a global consultation. The Charter followed the concept developed by the Poseidon Principles of creating globally agreed common baselines that can act as established minimum standards for reporting emissions in shipping. By making valuable asset-level climate alignment data available to signatories and disclosing the climate alignment of their chartering activities, the Sea Cargo Charter is supportive of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, the Global Logistics Emissions Council (GLEC) Framework, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the Energy Transitions Commission, and many other initiatives that are developing to address adverse impacts.

Background

The IMO (International Maritime Organization) is the United Nations’ specialised agency with responsibility for developing global standards for shipping applying to the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine and atmospheric pollution by ships.

The IMO approved an Initial Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Strategy in April 2018, prescribing that international shipping must reduce its total annual carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by at least 50% of 2008 levels by 2050, whilst pursuing efforts towards phasing them out as soon as possible in this century. Following this Initial Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Strategy, the IMO approved a revised Strategy on the reduction of GHG emissions from ships in July 2023 (available here).

This 2023 IMO GHG Strategy sets out the following levels of ambition:

1. to reduce the total annual GHG emissions from international shipping by at least 20%, striving

for 30%, by 2030, compared to 2008

2. to reduce the total annual GHG emissions from international shipping by at least 70%, striving

for 80%, by 2040, compared to 2008

3. GHG emissions from international shipping to peak as soon as possible and to reach net-zero GHG emissions by or around, i.e. close to 2050

Further terms that do not define GHG reduction rates, but are also in the revised level of ambition include:

4. emissions intensity of the ship to decline through further improvement of the energy efficiency for new ships

5. emissions intensity of international shipping to decline to reduce CO2 emissions per transport work, as an average across international shipping, by at least 40% by 2030, compared to 2008

6. uptake of zero or near-zero GHG emission technologies to represent at least 5%, striving for 10%, of the energy used by international shipping by 2030

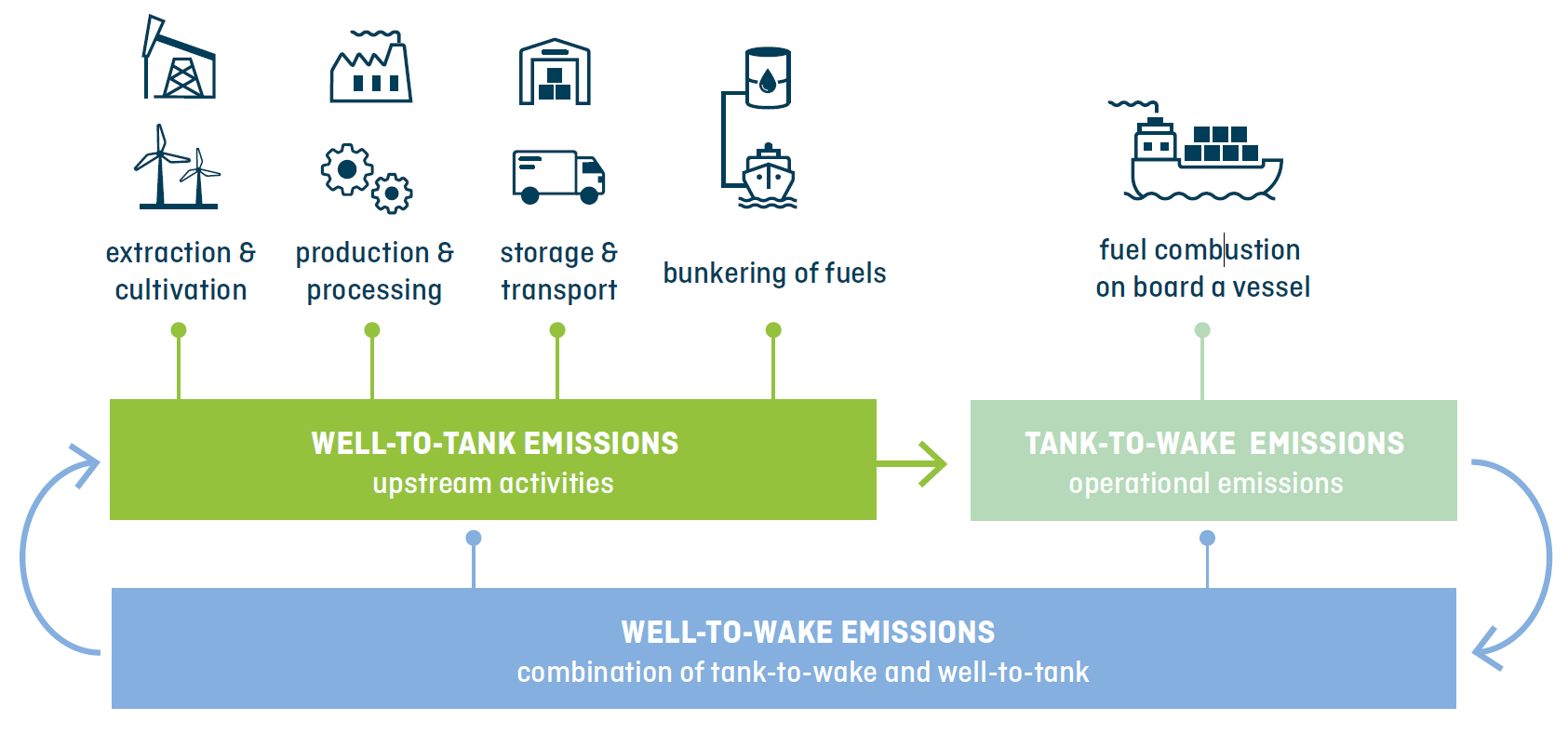

Moreover, any activity related to emission reduction and climate alignment in shipping will need to capture lifecycle emissions (well-to-wake approach) as well as all the relevant GHG species as specified by the IMO.

The Strategy also states that a basket of measure(s), delivering on the reduction targets, should be developed to promote the energy transition of shipping and provide the world fleet a needed incentive while contributing to a level playing field and a just and equitable transition.

According to the IMO’s Fourth GHG Study 2020, the sector accounted in 2018 for 2.89% of global anthropogenic emissions. Left unchecked, shipping emissions were expected to grow by 90-130% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels.

While CO2 represented almost all of the industry’s GHG emissions (98%), methane (CH4) emissions from ships increased over this period (particularly over 2009–2012) due to increased activity associated with the transport of gaseous cargoes by liquefied gas tankers due to methane slip. There is potential for this trend to continue in the future if shipping moves to liquefied natural gas (LNG) powered ships.

Nations pledged in the 2015 Paris Agreement “to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of GHG in the second half of this century” (UNFCC, 2015). This means getting to “net zero emissions” between 2050 and 2100. 2050 therefore represents a key milestone in the Paris Agreement, which the IMO explicitly references in its Strategy. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has quantified this target through a specific limit to a global temperature rise due to anthropogenic emissions of not more than 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels.

The 2023 IMO GHG Strategy alone does not secure a1.5°C future as set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The Sea Cargo Charter

The Sea Cargo Charter is a framework for assessing and disclosing the climate alignment of chartering activities of charterers and shipowners. While the Sea Cargo Charter has from its inception been opened to charterers, recognising the key role played by shipowners in the decarbonisation of shipping, the Sea Cargo Charter adapted its framework in 2024 to also allow shipowners who do not necessarily charter-in vessels to join. The Sea Cargo Charter creates common global baselines that are consistent with and supportive of society’s goals to better enable charterers and shipowners to measure and align their chartering activities with responsible environmental impacts. The four principles constituting the Sea Cargo Charter are:

- Assessment

- Accountability

- Enforcement

- Transparency

The Sea Cargo Charter

The Sea Cargo Charter sets a standard for reporting emissions, thus enhancing transparency and creating a global baseline to support and work towards the greater goals for our society and the goal to align charterers’ and shipowners’ maritime activities to be environmentally responsible. The objective is to unite a group of aligned and committed maritime players to take ownership of a set of principles to integrate climate considerations into charterparties, consistent with the climate-related goals of the IMO.

The Charter aims to be voluntary, practical to implement, verifiable, fact-based, and effective. Signatories commit to implementing the Charter in their internal policies, procedures, and standards.

The Charter is intended to evolve over time following a regular review process to ensure that the Charter is practical and effective, is linked to and supports the IMO’s GHG measures developed over time, and that further environmental factors are identified for inclusion as relevant.

The Sea Cargo Charter

Principle 1 – Assessment

This principle provides step-by-step guidance for measuring the climate alignment of signatories’ activities with the agreed climate target. It establishes a common methodology for calculating the emissions intensity and total GHG emissions, and thus also provides the input needed to track the decarbonisation trajectories used to assess signatories’ alignment.

Principle 2 – Accountability

To ensure that information provided under the principles is practical, unbiased, and accurate, it is crucial that signatories only use reliable data types, sources, and service providers.

Principle 3 – Enforcement

This principle provides the mechanism for meeting the requirement of the Sea Cargo Charter. It also includes a recommended charter party clause, the Sea Cargo Charter Clause, to ensure data collection. While the wording of the Sea Cargo Charter Clause is strongly recommended, it is not

compulsory for signatories.

Principle 4 – Transparency

The intent of the transparency principle is to ensure both the awareness of the Sea Cargo Charter and that accurate information can be published by the Secretariat in a timely manner. Furthermore, transparency is key in driving behavioral change.

The Sea Cargo Charter

Climate alignment is currently the only environmental factor considered by the Sea Cargo Charter. This scope will be reviewed and may be expanded by signatories on a timeline that is at their discretion.

All charterers and shipowners that the fulfill below criteria are eligible to join the Sea Cargo Charter:

- The Sea Cargo Charter welcomes all charterers and shipowners of ships in the dry bulk and tanker trades.

- Eligible companies to join the Sea Cargo Charter are companies that occupy any position along the charterparty chain: charterers, sub-charterers, disponent owners with commercial control, registered owners with commercial control.

- Companies that are not eligible for membership are (a) third-party management companies, which have no corporate relationship with the shipowning entity; and (b) shipowning entities that charter out the ship on bareboat charterparty terms.

The Sea Cargo Charter must be applied by signatories in all bulk chartering activities that are:

- on time and voyage charters, including contracts of affreightment and parceling, with a mechanism to allocate emissions from ballast voyages,

- for voyages carried out by dry bulk carriers, chemical tankers, oil (crude and product) tankers, and liquefied gas carriers,

- and where a vessel or vessels are engaged in international trade (excluding inland waterway trade).

Until 31 December 2021, vessels under 5000 gross tonnage (GT) were excluded and have since then been included. Voyages conducted on general cargo vessels are included in the scope of reported voyages when carrying dry bulk cargoes.

Eligible companies that fulfil the criteria of both charterers and shipowners shall declare annually the basis upon which they report their voyages (charterer or shipowner).

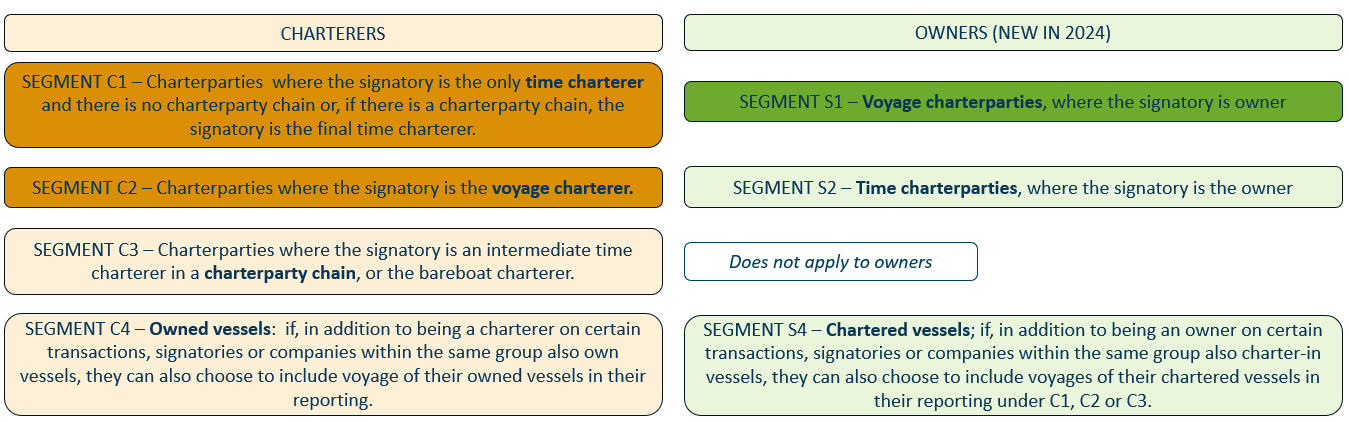

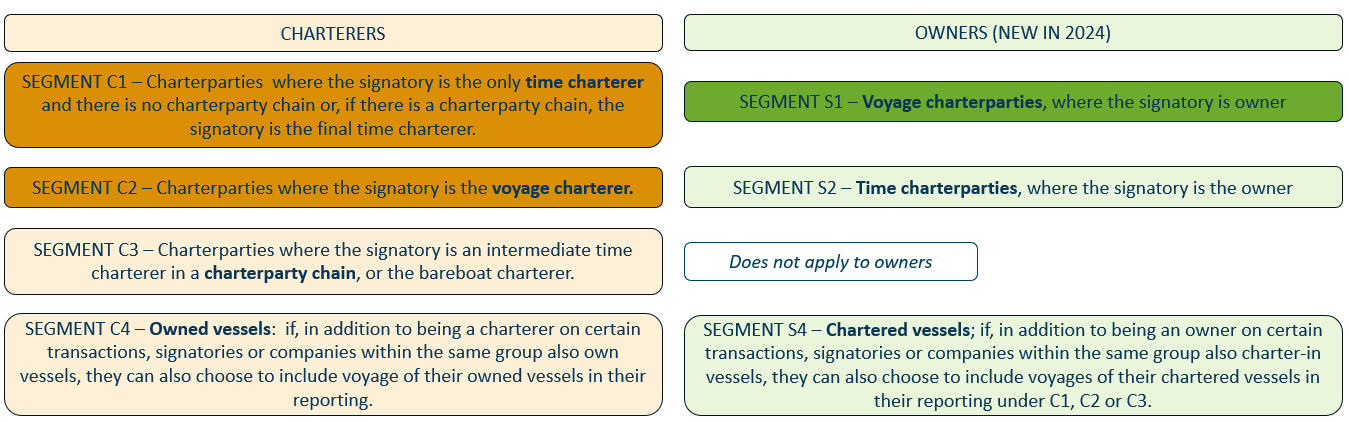

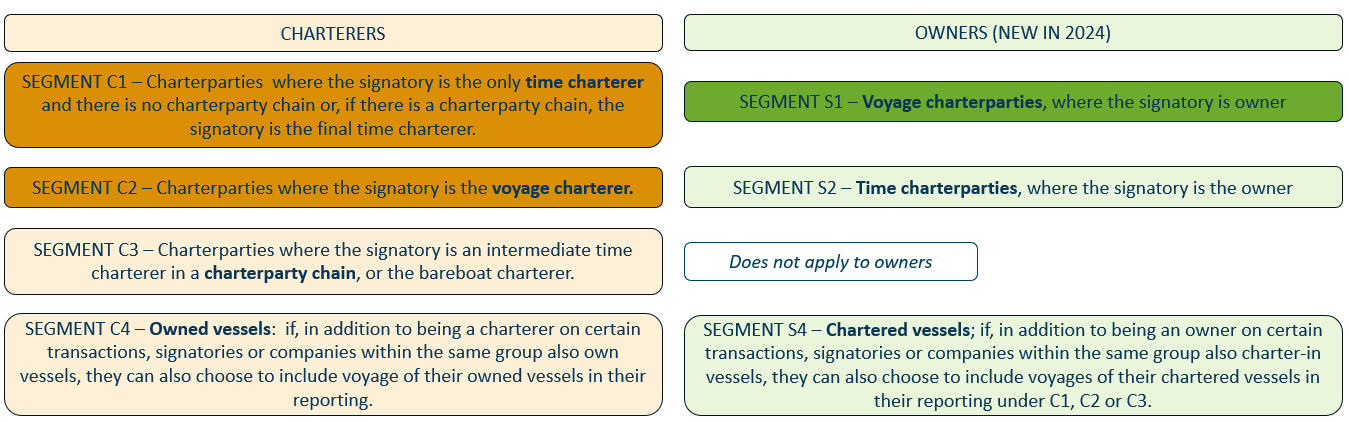

In recognition of the diversity of signatories, the Sea Cargo Charter follows a twin approach: firstly, flexibility as to the signatories’ choice of reporting segments, so as to encourage the widest adoption possible; secondly, certain minimum reporting requirements so as to maximise impact. This resulted in several reporting segments for signatories, depending on whether they report primarily as a charterer (Segments C1-C4) or as a shipowner (Segments S1-S4).

The Sea Cargo Charter

For signatories reporting primarily as charterers:

- SEGMENT C1: Charterparties where the signatory is the only time charterer and there is no charterparty chain or, if there is a charterparty chain, the signatory is the final time charterer.

- SEGMENT C2: Charterparties where the signatory is the voyage charterer.

- SEGMENT C3: Charterparties where the signatory is an intermediate time charterer in a charterparty chain, or the bareboat charterer.

- SEGMENT C4: Owned vessels: if, in addition to being a charterer on certain transactions, signatories or companies within the same group also own vessels, they can also choose to include voyage of their owned vessels in their reporting.

Segments C1 and C2 are mandatory. Segment C3 is optional. Segment C4 is optional and only open to signatories who are also reporting in Segments C1-3.

For signatories reporting primarily as shipowners:

- SEGMENT S1: Voyage charterparties, where the signatory is the owner.

- SEGMENT S2: Time charterparties, where the signatory is the owner.

- SEGMENT S4: Chartered vessels; if, in addition to being an owner on certain transactions, signatories or companies within the same group also charter-in vessels, they can also choose to include voyages of their chartered vessels in their reporting under C1, C2, or C3.

Segment S1 is mandatory, Segments S2 and S3 are voluntary.

As of the Annual Disclosure Report 2026 (reporting on 2025 data) segments C4 and S4 will become mandatory, unless a voyage is time-chartered out.

The Sea Cargo Charter

The Sea Cargo Charter was initially launched at the Global Maritime Forum Virtual High-Level Meeting on 7 October 2020.

The Sea Cargo Charter

The Sea Cargo Charter was until 2023 aligned with the ambition set by the IMO in its Initial Strategy in 2018 with a target of at least 50% reduction of CO2 emissions by 2050, on 2008 levels. At MEPC 80 in July 2023, a revised Strategy was put in place introducing higher ambition as well as differences in the emission boundaries to be considered. There are four main elements that changed with the adoption of the new trajectories:

- Addition of a minimum trajectory set with interim targets of 20% GHG reduction in 2030 and 70% GHG reduction in 2040 relative to 2008

- Addition of a striving trajectory set with interim targets of 30% GHG reduction in 2030 and 80% GHG reduction in 2040 relative to 2008

- Both these trajectories are set with a net-zero GHG target in 2050

- Both these trajectories’ GHG reduction targets are to be on a well-to-wake CO2e perspective

The Sea Cargo Charter

Workshops and presentations were held in late 2018-early 2019 in Singapore and Geneva to elicit feedback from a wide group of stakeholders (charterers and shipowners) on the development of the Sea Cargo Charter. The development of the Sea Cargo Charter was led by a drafting group constituted in October 2019 and chaired by Jan Dieleman, President of Cargill Ocean Transportation. The drafting group was spearheaded by representatives from all major segments in the industry – Anglo American, Dow Chemical, Euronav, Norden, Stena Bulk, Total, Trafigura – with support from Stephenson Harwood and in collaboration with the Global Maritime Forum, UMAS, and Smart Freight Centre.

The Sea Cargo Charter

Shipowners of varying sizes and geographies have been engaged and consulted throughout the process of developing the Sea Cargo Charter and some shipowners were members of the drafting group.

The Sea Cargo Charter

The Global Maritime Forum, Smart Freight Centre, and UMAS have been part of this work since its inception. They have also been working with other initiatives – such as the Poseidon Principles and the Poseidon Principles for Marine Insurance – to ensure that various initiatives within the shipping sector are compatible and impactful.

A broader group of NGOs and other stakeholders have been kept informed throughout the process.

The Sea Cargo Charter

The ambition to develop the Sea Cargo Charter finds its source in the very early stages of the Poseidon Principles for financial institutions. Since the launch of the Sea Cargo Charter in 2020, the Poseidon Principles for Marine Insurance have also been created under a similar framework.

The four core principles are the same for all three initiatives, but the frameworks rely on different metrics. The Poseidon Principles and the Poseidon Principles for Marine Insurance use the Annual Efficiency Ratio (AER) and can, therefore, rely on the IMO DCS to collect data, while the Sea Cargo Charter uses the Energy Efficiency Operational Indicator (EEOI) and thus have a different approach to source data.

The Sea Cargo Charter

The signatories of the Sea Cargo Charter decided to align the Association’s decarbonisation trajectory with the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy, reporting against both the ‘minimum’ and the ‘striving’ targets and the interim checkpoints of 2030 and 2040. This means that, contrary to the previous Annual Disclosure reports, signatories will now report against a new ambition and two baselines, the ‘minimum’ and the ‘striving’ baselines. Furthermore, the changes involve including the impact of other GHG species besides carbon dioxide (CO2), as the signatories will move to a more granular approach considering the full life cycle approach of emissions (move from tank-to-wake to well-to-wake) and all GHG species.

- Well-to-tank emissions: These are emissions produced via upstream activities, including extraction, cultivation, production, processing, storage, transport, bunkering of fuels.

- Tank-to-wake emissions: Or “operational emissions”; emissions produced via fuel combustion on board a vessel.

- Well-to-wake emissions: Or the “full lifecycle” emissions; this account for the all emissions produced from both upstream activities (tank-to-wake) as well as operation of a vessel.

The Sea Cargo Charter

Signatories to the Sea Cargo Charter recognise that the Charter is intended to evolve over time and agree to contribute to a review process when they, as signatories, decide to undertake it. This process will ensure that the Sea Cargo Charter is practical and effective, is linked to and supports the goals set by the IMO, and that further adverse impacts are identified for inclusion. The most recent updates are the following:

To align with the ambition in the IMO GHG Strategy from July 2023, the Sea Cargo Charter has updated its ambition and decarbonisation trajectory to align with it and is reporting for the first time against this new ambition in 2024. The Sea Cargo Charter was, until 2023, aligned with the ambition set by the IMO in its Initial Strategy in 2018 with a decarbonisation trajectory based on a target of at least 50% operational (tank-to-wake) CO2 reduction by 2050 on 2008 levels. At MEPC 80 in July 2023, a revised GHG Strategy was adopted introducing a higher ambition as well as differences in the emission boundaries to be considered. The Sea Cargo Charter has implemented this revision to bring its existing methodology in line with the new ambition levels, indicative checkpoints and emission boundaries set by the IMO. This revision entails including reporting full lifecycle (well-to-wake) emissions in terms of CO2e emissions (which includes non-CO2 GHG species, methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), in addition to CO2).

Furthermore, while voluntary reporting of owned vessels had already been possible under the previous framework, the Sea Cargo Charter has expanded its scope in April 2024 to welcome shipowners, who do not necessarily charter-in vessels or wish to report primarily on their owned vessels to allow them to do so under a common framework with charterers. With this expansion, the Sea Cargo Charter is seeking to increase its impact by maximising transparency and collaboration between key players in the transition to decarbonised shipping by uniting owners and charterers under a common framework and methodology, allowing them to benchmark progress against shared baselines.

Signatories also recognise that more urgent action is needed to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C from pre-industrialised levels and that shipping has a crucial role to play. While the latest revision to align with the revised IMO GHG Strategy from 2023 brings the Sea Cargo Charter’s ambition closer, is not yet aligned to a 1.5°C future as set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Furthermore, the IMO MEPC timetable currently has a mandated review of the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy in 2028. In 2025, it is likely that the Fifth IMO GHG Study will be published which will give an opportunity to reevaluate the impact on the Sea Cargo Charter. Next steps will also include assessing the IMO Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) guidance which will provide industry accepted well-to-wake emission factors and CO2e factors.

The Sea Cargo Charter

In January 2025, the emission factors were updated to reflect the latest available sources, including new IMO emission factors. As a result, the decarbonisation trajectories were adjusted to match these updated emission factors.

The Sea Cargo Charter

CO2e, or carbon dioxide equivalent, is a metric used to express the total impact of various greenhouse gases in terms of their equivalent contribution to global warming, measured in terms of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a specified timeframe. In terms of the Sea Cargo Charter, it allows for a standardised warming potential of methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), along with CO2, by expressing their collective impacts on climate change in CO2 equivalent (CO2e) units. Therefore, while CO2 is a specific greenhouse gas, CO2e provides a comprehensive measure that encompasses the diverse contributions of these gases collectively, facilitating a more inclusive assessment of overall greenhouse gas emissions.

Becoming a Signatory

The Sea Cargo Charter is applicable to charterers and shipowners that are: dry and wet bulk charterers, sub-charterers, all charterers in a charterparty chain, as well as disponent owners and registered owners with commercial control.

Becoming a Signatory

The Sea Cargo Charter was developed in recognition of charterers’ and shipowners’ roles in promoting responsible environmental stewardship throughout the maritime value chain. Signatories will be recognised for contributing to an initiative that is ground-breaking in both sustainable shipping and transparency.

Becoming a signatory of the Sea Cargo Charter shows commitment to transparency and emission reporting in shipping. Signatories contribute to a standardised method to measure climate alignment in a way that is useful for the industry for meeting the IMO’s ambition and to exchange information between shipowners and charterers. This does not only allow signatories to benchmark their progress against shared baselines with other key players in the industry based on international standards but also provides them with a better understanding of their emissions related to their chartering activities, which have become increasingly important in their relationship with business partners, lenders, shareholders, etc.

Signatories will also gain access to valuable asset-level information that can be used to build organisational learning, assess progress in decarbonisation efforts and potential climate risks that may impair returns in the future.

Becoming a Signatory

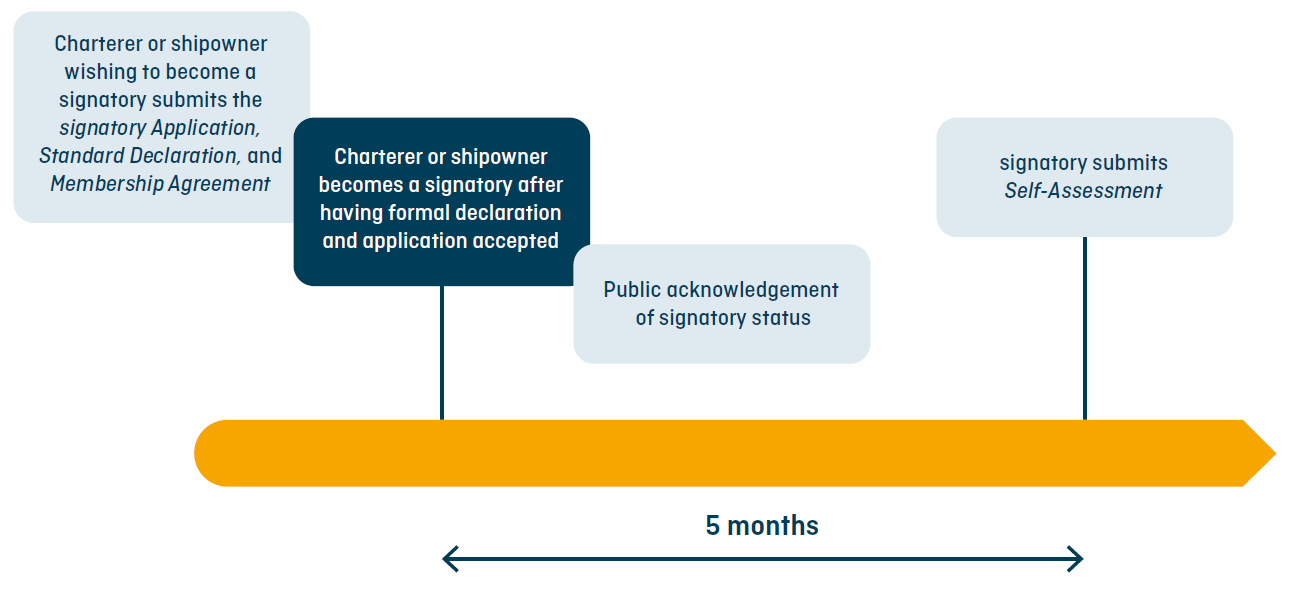

Organisations wishing to become a signatory of the Sea Cargo Charter must submit the Standard Declaration, Signatory Application, and Membership Agreement to the Secretariat of the Sea Cargo Charter Association. Once accepted into the Association, the signatory has five months to complete and submit the Self-Assessment to the Secretariat. All documents are available from the Secretariat.

Becoming a Signatory

The Standard Declaration is the formal commitment required to become a signatory. It announces the intent of the signatory to follow all requirements of the Charter. The Standard Declaration is available from the Secretariat.

Becoming a Signatory

Along with the Standard Declaration, an Organisation wishing to become a signatory must complete the Signatory Application Form. This document outlines who is responsible for contact, reporting, invoicing, and other necessary functions to implement and maintain the Sea Cargo Charter within the signatory’s Organisation. The Signatory Application Form is available from the Secretariat.

Becoming a Signatory

The third document an Organisation must submit in order to become a signatory to the Sea Cargo Charter is the Membership Agreement. This document outlines legal obligations for signatories and rules of the Sea Cargo Charter Association, which signatories are automatically members of. The Membership Agreement is available on the website.

Becoming a Signatory

The purpose of the Self-Assessment is to ensure that each signatory has made appropriate arrangements to fulfil its obligations under the Sea Cargo Charter and identified any challenges in doing so. The Self-Assessment is as brief as possible to reduce the administrative burden, while still addressing the core responsibilities of signatories to the Sea Cargo Charter. The Self-Assessment questions are available from the Secretariat.

Becoming a Signatory

The Sea Cargo Charter is designed from and in line with the Poseidon Principles and is also intended to support other initiatives, such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, the Global Logistics Emissions Council (GLEC) Framework, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Energy Transitions Commission, and the many others that are developing to address adverse impacts.

Becoming a Signatory

The signatory fee for 2024 is EUR 10,000 and is paid to the Sea Cargo Charter Association up becoming a signatory. The Annual Fee for 2024 is EUR 9,700 (Pending approval at the Annual Meeting 2025) and is paid annually to The Sea Cargo Charter Association in accordance with the Governance Rules. In the first year of becoming a signatory, the Annual Fee is required in addition to the Signatory Fee. Because the budget of the Sea Cargo Charter Association is set in euros, the fees are also collected in euros to avoid currency risks.

Becoming a Signatory

While the Sea Cargo Charter has from its inception been opened to charterers, recognising the key role played by shipowners in the decarbonisation of shipping, the Sea Cargo Charter adapted its framework in 2024 to also allow shipowners who do not necessarily charter– in vessels or wish to report primarily on their owned vessels to allow them to join. Therefore, the list of companies that are welcome to join the Sea Cargo Charters encompasses charterers and shipowners that are: dry and wet bulk charterers, sub-charterers, all charterers in a charterparty chain, as well as disponent owners and registered owners with commercial control.

Currently, there is not an official way to endorse or formally support the Sea Cargo Charter other than becoming a signatory. Please contact the Sea Cargo Charter Secretariat to register your interest so that you can be contacted should/when a pathway for membership or endorsement become available.

The Sea Cargo Charter recognises that there are different types of charterers and shipowners and wants to facilitate participation by giving signatories reporting options. The reporting is, therefore, divided into segments for charterers (C1-C4) and for shipowners (S1-S4) that ensure certain minimum reporting requirements so as to maximise impact while ensuring both flexibility and the widest adoption possible.

Segments C1 and C2 for charterers are mandatory and any data falling under these two segments shall be included in the eligible reporting chartering activities, if applicable. If a charterer is unable to report any of this data, they need to include that into percentage of eligible chartering activities non-reporting (which is disclosed internally). Segments C3 for charterers is optional. Segment C4 is optional and is only open to charterers who are also reporting in Segments C1-C3.

For shipowners, Segment S1 is mandatory and Segments S2-S4 are optional.

As of the Annual Disclosure Report 2026 (reporting on 2025 data) segments C4 and S4 will become mandatory, unless a voyage is time-chartered out.

Becoming a Signatory

The “preferred pathway” information flow in the Sea Cargo Charter methodology recommends the use of verification mechanisms (from third parties / service providers) to maintain data veracity. While the Sea Cargo Charter recognises the important role that verification mechanisms play in providing unbiased information to the industry, the Sea Cargo Charter Secretariat does not formally endorse any service provider. Signatories are free to work with any third party / service provider of their choice. It is their responsibility to ensure that the provider performs services for them using the latest available Sea Cargo Charter methodology.

Climate alignment

For the purposes of the Sea Cargo Charter, climate alignment is defined as the degree to which voyage emissions intensity of a vessel category is in line with a decarbonisation trajectory (provided by the Secretariat of the Sea Cargo Charter based on agreed and clearly stated assumptions) that meets the IMO’s goal of reaching net-zero GHG emissions by or around, i.e. close to 2050 compared to 2008 levels. Historically the Sea Cargo Charter has been aligned to the IMO’s initial level of ambition, which involved a 50% reduction of CO2 emissions from international shipping compared to 2008 levels. Following the IMO MEPC 80 meeting in July 2023, signatories unanimously decided in November 2023 to align with the IMO’s latest ambition in its 2023 Strategy – which aims for net-zero emissions from international shipping “by or around” 2050 compared to 2008 levels, with interim targets in 2030 and 2040, on a well-to-wake basis. Furthermore, the emissions boundary is now set at CO2e emissions which includes the impact of non-CO2 GHG species, methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), along with Carbon Dioxide (CO2).

Alignment means that the annual activity of a signatory is in line with the decarbonisation trajectories over time. This may not happen every year; however, one or two misaligned years do not mean that it is impossible for the annual activity to align. It may take time to establish a downward trend in line with the trajectory over time. This is especially relevant given the recent increase in ambition reflected in the updated decarbonisation trajectory post IMO MEPC 80 in 2023.

Climate alignment

Due to the changes in the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy and for the purpose of the Sea Cargo Charter, emissions intensity now represents the total GHG emissions (well-to-wake) to satisfy a supply of transport work (measured in grams of well-to-wake CO2e per tonne-nautical mile [gCO2e/tnm]).

Emissions intensity is typically quantified for multiple voyages over a period of time (e.g., a year). To provide the most accurate representation of a voyage’s actual climate impact, the emissions of a voyage should be measured from its performance in real conditions. This is done using a carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) intensity measure known as Energy Efficiency Operating Indicator (EEOI), reported in unit grams of CO2e per tonne-nautical mile (gCO2e/tnm). With the adoption of well-to-wake emission factors covering all greenhouse gases by the IMO, the original EEOI formula has been adjusted so that the mass of CO2 is replaced by the CO2 equivalent (CO2e). The CO2e is calculated by multiplying the mass of each greenhouse gas released to the atmosphere by its global warming potential so that the impact of all gases is expressed on an equivalent basis.

Climate alignment

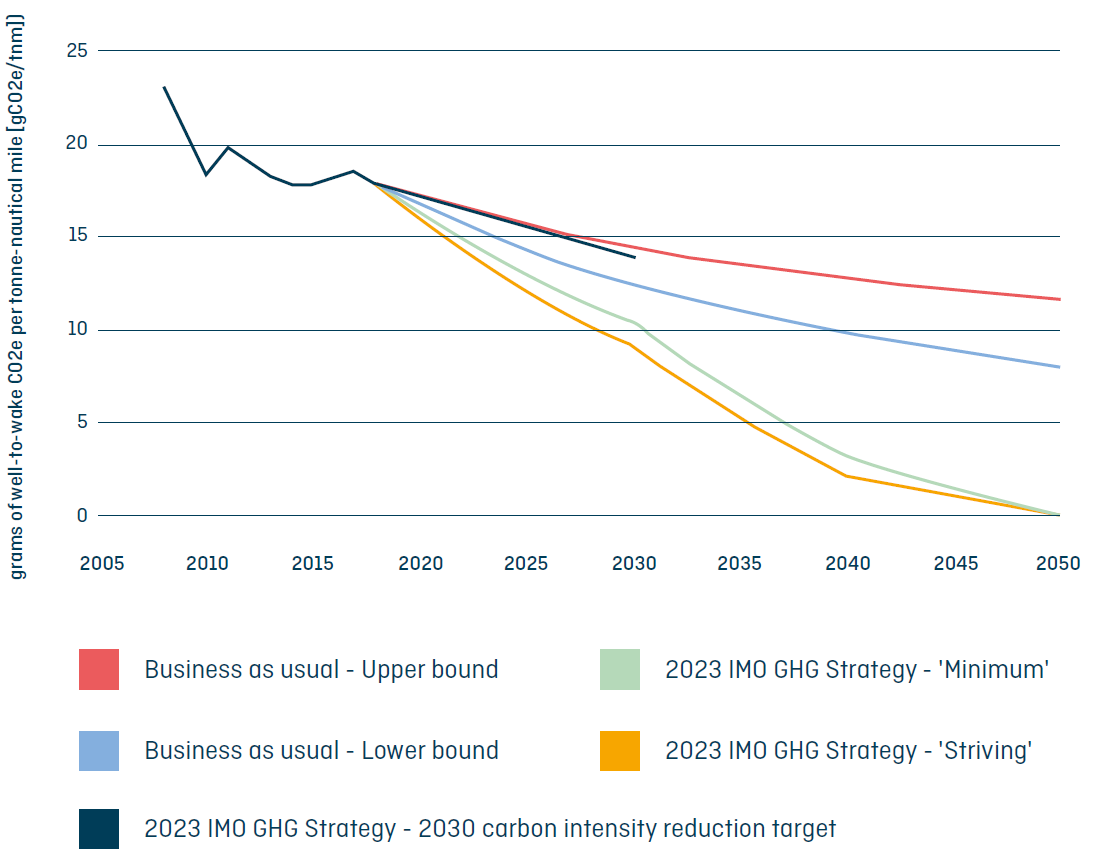

In the context of the Sea Cargo Charter, decarbonisation trajectories are representations of how many grams of CO2e can be emitted to move one tonne of goods one nautical mile (gCO2e/tnm) over a time horizon to be in line with the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy ambition of reducing total annual well-to-wake emissions to net-zero around 2050. These also take into account interim checkpoints in 2030 (20% reduction, striving for 30% on 2008 levels) and 2040 (70% reduction, striving for 80% on 2008 levels).

The decarbonisation trajectory represents the emissions intensity reduction required to meet certain decarbonisation ambitions. For the purposes of the Sea Cargo Charter, and consistent with the current interpretation of the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy, the decarbonisation trajectories used were updated to consider:

- The “minimum” interim targets of 20% GHG reduction in 2030 and 70% GHG reduction in 2040 relative to 2008.

- The “striving” interim targets of 30% GHG reduction in 2030 and 80% GHG reduction in 2040 relative to 2008.

- A net-zero GHG target in 2050.

- A well-to-wake carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) perspective.

The overall decarbonisation trajectories are applied to each vessel category’s using 2012 IMO data providing specific values for each ship type and size because emission intensities vary as a function of ship type and size, as well as a ship’s technical and operational specification. The trajectory is used to help measure the alignment of vessels and cargo of signatories.

Global fleet’s emission intensity targets and trajectories defined by the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy (grams of well-to wake CO2e per tonne-nautical mile [gCO2e/tnm])

Climate alignment

The Secretariat and official Advisors of the Sea Cargo Charter Association provide the standard decarbonisation trajectories based on agreed and clearly stated assumptions derived from emission and transport work data from the Fourth IMO GHG Study. Updates are undertaken regularly based on updated internationally agreed ambitions, best available data and scientific evidence.

The decarbonisation trajectories as updated by the Sea Cargo Charter in late 2023 are consistent with the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy to reduce emissions from ships. This alone does not secure the Paris Agreement’s well below 2°C global mandate and efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5°C.

The most recent update in January 2025 ensured that the trajectories align with the latest emission factors used for reporting.

Climate alignment

The target emissions intensity in a given year is calculated as a function of the ship type and size as explained in Appendix 4 of the Technical Guidance. The emissions intensities of individual ship types and sizes are estimated based on the median EEOI values from the Fourth IMO GHG Study. The Sea Cargo Charter uses continuous required emissions intensity baselines for each vessel type and size. The required emissions intensity is expressed as follows:

?? = (?. ?ear3 + ?. ?e??2 + ?.Year + ?). Sizee

Where rs is the required emissions intensity, Year is the year for which the emissions intensity is required, and Size is the size of the vessel in question in deadweight or capacity. The coefficients a, b, c, d, and e arise from the fitted curves and differ for each vessel type. Their values can be found in Table 7 of the Technical Guidance.

Climate alignment

The annual alignment can be improved by operating vessels in a more efficient manner and by chartering vessels with lower emissions intensity through better–performing vessels, more efficient operation, or higher utilisation efficiency. By implementing operational efficiency measures, such as slower vessel speeds, optimised arrivals at ports, weather routing, etc. signatories can improve the annual climate alignment through more efficient fuel consumption. For examples of operational efficiency measures being taken already today, explore the report “Taking Action on Operational Efficiency” by the Global Maritime Forum.

Climate alignment

Being a signatory to the Sea Cargo Charter does not preclude the use of emissions offsetting, but these are not considered when reporting emissions and assessing climate alignment under the Sea Cargo Charter: the full extent of operational emissions is captured in the assessment of climate alignment.

Climate alignment

The impact of retrofits, improved ship design, and operational efficiency measures is accounted for through fuel consumption relative to the transport work carried out.

Climate alignment

Various metrics assess climate alignment, such as the EEDI (Energy Efficiency Design Index) based on vessel design characteristics, the AER (Annual Efficiency Ratio) or the EEOI (Energy Efficiency Operating Indicator), tied to operational carbon intensity. The Poseidon Principles for Financial Institutions and Marine Insurance use AER and can therefore rely on the IMO DCS to collect data, while the Sea Cargo Charter reports on the basis of EEOI and thus has a different approach to source the data.

The Sea Cargo Charter employs the EEOI (adapted to reflect CO2 equivalent (CO2e) emissions, aiming for a precise measure of a vessel’s emissions intensity during operation. Required data includes fuel consumption, GHG emission factors, distance travelled, and cargo transported. AER is used by Poseidon Principles for Financial Institutions and Marine Insurance, striving for alignment with IMO policies and regulations, albeit less accurate than EEOI due to cargo variations which are more easily accessible to charterers and shipowners.

Climate alignment

The impact of operational efficiency measures is accounted for through fuel consumption relative to the transport work carried out.

Climate alignment

Typically, older vessels have higher fuel consumption meaning that emissions intensity may be higher; however, operational efficiency is also an important factor which may make up for the older technology. For examples of operational efficiency measures being taken already today, explore the report “Taking Action on Operational Efficiency” by the Global Maritime Forum.

Calculations & data sourcing

The emissions intensity metric – EEOI – requires the following data to compute it:

- The amount of fuel consumed for each type of fuel in metric tonnes (over both ballast and laden legs)

- The GHG emissions factor of each fuel type

- Actual distance travelled in nautical miles (while laden with transported cargo)

- Amount of cargo transported in metric tonnes over the given voyage as per the bill of lading (for liquified gas carriers, the amount of cargo discharged is to be used for the

calculation of emissions intensity).

Signatories are only allowed to use measured data to calculate their climate alignment – no estimates. If, and only if, measured data can’t be sourced for ballast legs, the signatory will source estimated data exclusively for ballast legs.

Calculations & data sourcing

Measured voyage data and related noon reports or voyage reports must be sourced from the owners for each voyage under voyage charter. For charterers, data must be gathered by the signatory for each voyage under time charter, and requested and gathered from shipowners for each voyage under voyage charter. Shipowners are expected to already have all the necessary data for both time and voyage charters and therefore do not need to source additional data. However, they are encouraged to get the consent of their charterer counterparts to use the data for the Annual Disclosure Report when relevant.

The recommended charter party clause – the Sea Cargo Charter Clause (available on the website) – ensures that appropriate data and information is requested by and provided to signatories by their contractual counterparties, the appropriate consents are given for the sharing of data, and appropriate privacy protections are established.

Calculations & data sourcing

In order for all the actual emissions related to the transport work to be accounted for, the emissions from the previous ballast leg are to be included when calculating emissions intensity. All ballast legs are accounted for in the calculations as estimated data must be sourced for missing ballast leg if measured data can’t be sourced. Ballast legs is the only case where estimated data is allowed. It can be sourced either from the Automatic Identification System (AIS), by extrapolation from actual ballast legs for other voyages/vessels, or from a distance or voyage calculator.

Calculations & data sourcing

The IMO Initial Strategy captured operational (tank-to-wake) emissions, whilst the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy refers to lifecycle (well-to-wake) emissions. To comprehensively measure a ship’s total emissions, upstream and operational emissions have been combined, which prevents issues arising from emissions “leakage” due to fuels which have zero operational emissions but higher emissions when their upstream emissions are counted.

To allocate upstream well-to-tank emission factors, assumptions regarding vessel technologies, fuel feedstocks and production processes must be made as currently no set of widely accepted emission factors are in place for non-conventional fuel. This is less of a problem for conventional maritime fossil fuels.

The most pertinent for the purposes of the maritime industry is the lifecycle assessment (LCA) Guidelines1 that is revised by the IMO.

These LCA guidelines should provide a widely accepted framework for defining emission factors in the industry. However, as the latest update to the IMO LCA Guidelines was not yet available for the 2024 reporting period (2024 report based on 2023 data), the Sea Cargo Charter adopted a set of emission factor for reporting that captured the latest available science, provided transparency, captured upstream emissions and the impact of onboard technologies. Several national and supranational entities have published emission factors to cater for their internal regulatory framework and emissions accounting all of which have advantages and disadvantages with no clear gold standard.

The main sources consulted were the provisional EPC.376(80), material from the European Commission outlining reporting under Fit for 55 regulation (Fuel EU), the ecoinvent database, as well as the GREET framework used in the US. With this information at hand and keeping the logic that transparency will be key to ensure legitimacy and credibility for any pragmatic way forward, the following cascading order of emission factor priority has been adopted:

- Emission factors for conventional liquid fuels available in MEPC.376(80) should be used

- All other emission factors should be taken from the Fuel EU/ecoinvent database

- Any other emission factors should be taken from the GREET database.

A complete list of default and more granular emission factors can be found in Tables 8.1 and 8.2 of the Sea Cargo Charter’s Technical Guidance.

For biofuels, signatories should also use the given default factors. However, if signatories have access to widely recognised certified factors (such as from RSB, REDcert, ISCC), they can be used for the reporting (in the 2024 Annual Disclosure report based on 2023 data). This will be reassessed for future reporting periods.

Calculations & data sourcing

Given that the aim of the Sea Cargo Charter is not to create an absolute emissions inventory, there is no risk of accounting for the same emissions’ multiple times. Using emissions intensity as a metric precludes this problem from occurring.

Calculations & data sourcing

The data required for emissions intensity calculation is already readily available to vessel operators as it is collected for operational purposes and the keeping of mandatory logs. Therefore, no problems are envisaged with regard to data availability, although data requests and sharing may take time to be implemented; the recommended Sea Cargo Charter Clause ought to ease this process.

Signatories typically collect data on an ongoing basis so, it is expected that they will have collected all needed data by 31 January for the last voyages of the previous year.

Calculations & data sourcing

Charterer signatories are well within their rights to ask their business partners for this information and are usually able to source the data that is needed. As the Sea Cargo Charter has developed, business partners of signatories’ have also become more accustomed with the entailed data collection process. Message toward business partners is a document available on the Resources page of the website to support signatories of the Sea Cargo Charter in their relation with their business partners they will be requesting information from. This document aims at providing business partners with an overview of the Sea Cargo Charter, which data will the signatory request, and how this data will be treated.

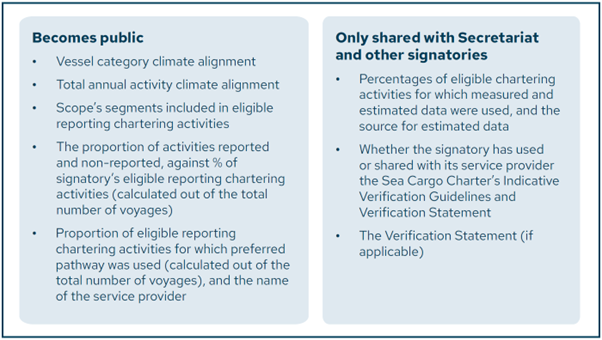

However, it is recognised that collecting 100% of relevant data may not be possible in some circumstances. In this instance, signatories are required to disclose the percentage of their eligible reporting chartering activities (calculated out of the total number of voyages) for which they have non-disclosure. This information is available to other signatories but not disclosed publicly. Table 4 in the Technical Guidance of the Sea Cargo Charter provides an example of this.

Calculations & data sourcing

There is no minimum threshold, but signatories are required to disclose the percentage of the eligible reporting chartering activities for which there is non-disclosure. Experience over the first years of reporting has shown that a vast majority of signatories report more than 90% of their chartering activities. If there are significant inconsistencies, it will fall to the governance system to determine how to address the issue. This is to preserve the integrity and legitimacy of the Sea Cargo Charter as this percentage is expected to improve over time.

How is data verified and incorrect data treated?

To ensure that subsequent alignment calculations are based on the correct inputs, the Sea Cargo Charter Association encourages use of the standard Data Collection Templates available on the Resources page of the Sea Cargo Charter’s website the which have strong validation rules covering the data values and format to minimise low level reporting errors at source. This applies however Sea Cargo Charter signatories perform their climate alignment calculations.

Guidance on how to proceed in case of incorrect data received from owners can be found in the Technical Guidance:

- Signatories are to ensure that obvious errors are corrected at source (vessels/shipowners from where the data originated). If data can’t be corrected at source, it should be categorised and reported under the percentage of eligible chartering activities non-reporting.

- No filters/omission should be applied to voyage EEOI result calculation for the higher order reporting (vessel category and total annual climate alignments) if the input raw data for voyages are correct (i.e., distance, cargo, consumption etc.).

The Technical Guidance also sets broader requirements for each information flow step.

After their first two reporting cycles a signatory is notably required to apply the ‘Preferred Pathway Track’ instead of the ‘Allowed Pathway Track’ as detailed in the Technical Guidance, which requires at the minimal extent to involve a third party verifier. Signatories that were already members of the Sea Cargo Charter by the time that decision was made (in November 2022), can take another year before moving to the ‘preferred pathway track’ and as such are only obliged to do so at the latest by the 2025 report on 2024 data. It remains the signatory’s responsibility to follow the Sea Cargo Charter’s Technical Guidance and apply its own methodology for the verification in areas where the Technical Guidance allows for flexibility, as well as ensuring that procedures are documented and internally quality-checked. In addition, and with a view to strengthen the verification process and enhance consistency, the Sea Cargo Charter has also developed Indicative Verification Guidelines provided to signatories for their and their service providers’ recommended use for the data verification and calculations.

Calculations & data sourcing

Emission factors have been developed by the Sea Cargo Charter’s advisories to be able to fully align with the ambition in the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy, while the IMO Is still working on its lifecycle assessment (LCA) guidance.

The following cascading order of emission factor priority has been followed:

- Emission factors approved by MEPC should be used, where available;

- All other emission factors, or relevant input parameters, should be taken from the Fuel EU/ecoinvent database where available;

- Any other emission factors should be taken from sources aligned with the GLEC framework emission factors.

The emission factors are provided for all fuel types listed in Table 8 of Appendix 4 in the Sea Cargo Charter Technical Guidance. In this table, fuels are first categorised under main fuel types, which are then further divided into subclassifications which include a default value for each fuel, or more detailed information for the fuel or the engine type, each with its own emission factor . For example, under the main category of Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO), emission factors are specified separately for default HFO, Very Low Sulfur Fuel Oil (VLSFO), and High-Sulfur Heavy Fuel Oil (HSHFO).

Owners collecting data under the DCS resolution rely on MEPC.308(73) for emission factors which are limited to eight generic conventional maritime fossil fuels. This implies that the Sea Cargo Charter signatories may not have access to the required information about fuel consumed and machinery on board to be able to report the most accurate emissions related to their activity. To this end, each fuel type in Table 8 has a designated default emission factor.

For the best possible representation of signatories’ portfolio performance, a comprehensive set of emission factors is provided for those that are able to obtain more granular information about fuels consumed and propulsion systems. Table 8 in the Technical Guidance provides a more granular set of emission factors which can be used by signatories.

For biofuels, including biofuel blends, signatories who have more specific information at their disposal are free to use more representative emission factors as long as they are compiled under a reputable scheme (such as RSB, REDcert, ISCC). Where signatories do not have specific information about the emission factor of the fuel they are using, default emission factors for selected biofuels and biofuel/fossil fuel blends are provided in Table 8. If the percentage of the blend is not known, signatories are to use the well-to-wake factor of the conventional fuel (i.e. LFO, HFO, MDO/MGO) that is blended with the biofuel.

Calculations & data sourcing

In order to increase the transparency and robustness of signatories’ data, the Sea Cargo Charter Association is striving to continuously strengthen the verification of signatories’ data and calculations.

To that end, after their first two reporting cycles a signatory is notably required to apply the ‘Preferred Pathway Track’ instead of the ‘Allowed Pathway Track’ as detailed in the Technical Guidance, which requires at the minimal extent to involve a third party verifier. Signatories that were already members of the Sea Cargo Charter by the time that decision was made (in November 2022), can take another year before moving to the ‘preferred pathway track’ and as such are only obliged to do so at the latest by the 2025 report on 2024 data. It remains the signatory’s responsibility to follow the Sea Cargo Charter’s Technical Guidance and apply its own methodology for the verification in areas where the Technical Guidance allows for flexibility, as well as ensuring that procedures are documented and internally quality-checked. In addition, and with a view to strengthen the verification process and enhance consistency, the Sea Cargo Charter has also developed Indicative Verification Guidelines provided to signatories for their service providers’ recommended use for the data verification and calculations.

Third parties are encouraged to verify the data and perform calculations using the Sea Cargo Charter’s Indicative Verification Guidelines as provided by the respective signatory. They can confirm the verification by using a verification statement template created by the Sea Cargo Charter Association and provided by the signatory.

Enforcement of the Charter

The enforcement process is outlined in the Technical Guidance and is the primary guide for meeting the requirements of the Sea Cargo Charter. The Secretariat in conjunction with the Steering Committee, as outlined in the Charter and the Governance Rules, updates the Technical Guidance when relevant to ensure the Sea Cargo Charter is up to date.

Enforcement of the Charter

It was at the request of the drafting group and shipowners that were consulted that the Sea Cargo Charter should include a recommended charterparty clause to request data from owners so that charterers do not have to negotiate similar wording with every business partner.

The Sea Cargo Charter Clause provides a suggestion to charterer signatories about how to request the data required to calculate climate alignment at the voyage level from shipowners. Incorporating this Clause within charterparties will guarantee collection of the necessary data in a harmonised way across the activities of all signatories.

With the scope expansion to shipowners, the Clause has been further amended to include relevant provisions for owners. As shipowners should already have all the necessary data at hand to calculate their climate alignment, the relevant paragraph in the clause specifies that charterers should provide their consent in owners using the data for the purpose of the Sea Cargo Charter.

To support data collection, various Data Collection Templates have been developed.

While the Clause wording is strongly recommended, it is not compulsory for signatories. However, if all signatories start using it in new contracts it will de facto be in common usage. The Sea Cargo Charter Clause and Data Collection Templates are available on the website.

Reporting & transparency

Signatories annually assess climate alignment in line with the Technical Guidance for all eligible reporting chartering activities. This means that signatories calculate the emissions intensity of voyages in order to assess vessel category climate alignments (by ship type and size) and their total annual activity climate alignment, using measured data and decarbonisation trajectory/ies provided by the Secretariat.

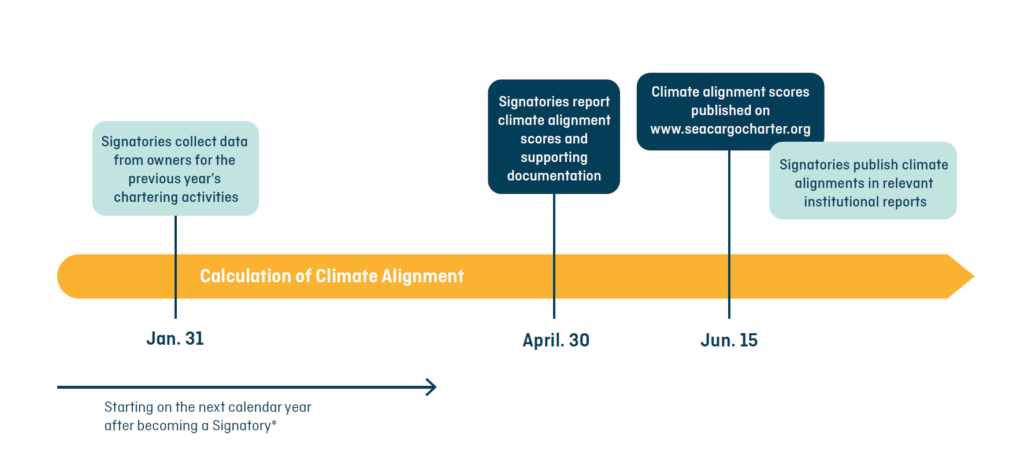

The timetable for implementation below highlights when there are important deadlines for alignment and reporting to comply with the Sea Cargo Charter.

The first calendar year of reporting, the signatory reports on its chartering activities for the previous year (year of becoming a signatory), starting from the next fiscal quarter date after the date of becoming a Signatory. Fiscal quarters starting dates are set as follows: Q1 – January 1, Q2 – April 1, Q3 – July 1, Q4 – October 1. Starting from the second calendar year of reporting, the signatory reports on the entire previous calendar year.

Reporting & transparency

The following is the data signatories are required to report, divided into two categories depending on whether the data gets published publicly or remains confidential within the Association:

The signatory’s total annual climate alignment score, the alignment scores by categories, and the scope’s segments are published. On top of that, as of the Annual Disclosure Report 2025, the reporting percentage and information on which pathway was used, including the name of the verifier, will be made public. On top of that, as of the Annual Disclosure Report 2025, the reporting percentage and information on which pathway was used, including the name of the verifier, will be made public.

Reporting & transparency

The Sea Cargo Charter recognises that there are different types of charterers and shipowners and wants to facilitate participation by giving signatories reporting options. The reporting is, therefore, divided into segments for charterers (C1-C4) and for shipowners (S1-S4) that ensure certain minimum reporting requirements so as to maximise impact while ensuring both flexibility and the widest adoption possible.

Segments C1 and C2 are mandatory for charterers and any data falling under these two segments shall be included in the eligible reporting chartering activities, if applicable. If a charterer is unable to report any of this data, they need to include that into percentage of eligible chartering activities non-reporting (which is disclosed internally).

Segments C3 for charteres is optional. Segment C4 is optional and is only open to charterers who are also reporting in Segments C1-C3.

Segment S1 for shipowners is mandatory and any data falling under it shall be included in the eligible reporting chartering activities for shipowners. Segments S2-S4 are optional for shipowners.

As of the Annual Disclosure Report 2026 (reporting on 2025 data) segments C4 and S4 will become mandatory, unless a voyage is time-chartered out.

Reporting & transparency

The main difference is that the European Union Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (EU MRV) and the IMO Data Collection System (IMO-DCS) are annual aggregations which do not offer the granular insight that reflects the day-to-day reality for charterers. The Sea Cargo Charter obliges reporting on a voyage basis thus providing emissions data that charterers can use to make better climate-aligned decisions.

Reporting & transparency

Every effort has been made to minimise the reporting requirements of the Sea Cargo Charter.

Governance

The Sea Cargo Charter Association manages, administers, and develops the Sea Cargo Charter.

The members of the Sea Cargo Charter Association are the signatories to the Sea Cargo Charter.

Governance

Steering Committee

The Steering Committee is comprised of 10 to 15 representatives of signatories to the Sea Cargo Charter, with one representative per signatory. One member will act as Chair, one member as Vice Chair, one member as Treasurer. Steering Committee members hold a senior position relevant for the Sea Cargo Charter. The Steering Committee leads the Annual Meeting and holds other meetings as necessary. Members of the Steering Committee are volunteers and are therefore not compensated by the Association. The list of members currently part of the Steering Committee can he found on the website.

Signatories

All signatories are members of the Sea Cargo Charter Association and are encouraged to participate in and contribute to the management of the Association in a manner that supports the Charter and is appropriate for their institution. The signatories who have become signatories will appoint a senior representative to join relevant meetings of the Association, such as the Annual Meeting. Just as with the Steering Committee, the representative must hold a position relevant to the Sea Cargo Charter. Signatories can nominate a representative from their institution to become a member of the Steering Committee. Nominees are then voted into positions by all signatories and serve a term in the Steering Committee as outlined in the Governance Rules.

Technical Committee

At the 2021 Annual Meeting, the signatories voted and agreed to establish the Technical Committee. Its role is to ensure methodological integrity of the Sea Cargo Charter within the scope agreed by the Steering Committee. The Technical Committee does not have decision making power; it formulates proposals which are then brought up to signatories. The Technical Committee is composed of a subset of signatories and is supported by the Advisory and Secretariat. Technical Committee members must hold appropriate technical background.

Governance

Secretariat

The role of the Secretariat is to maintain the day-to-day business and administration of the Steering Committee, Charter, and the signatories. The Secretariat serves a facilitating function in the Steering Committee, Technical Committee, and among signatories.

The Secretariat role can be fulfilled by a relevant non-profit and independent third-party entity. This role is currently fulfilled by the Global Maritime Forum.

Advisory

The Advisory advises and guides the technical discussions and expertise of the Charter, including creating and revising the scope of the Charter or the decarbonisation trajectory. It ensures the used methodology and data found in the Charter are current, relevant, and simple to implement for signatories. The Advisory is also involved in working groups and takes part in the Steering Committee or Technical Committee meetings as needed.

Current technical advisors are Smart Freight Centre and UMAS. The current legal advisor is Stephenson Harwood.